Renga is a masterpiece of lasers and co-op play

IndieCade is a festival celebrating the works of independent game designers from all over the world and this past weekend was Indiecade’s inaugural appearance on the east coast at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York City. Attending this game festival from a gamification angle, I was looking for new and exciting ways to engage with an audience.

One of the main events was the game Renga by UK-based WallFour, who specialize in live, large-scale collaborative crowdgames. In other words, when I read that Renga was going to be a feature-length game for 100 people with laser pointers, I was sold.

As I sat myself into the gorgeous main theater, we were told that we were going to work together, be as loud as we wanted, and that we had to share our laser pointers. And boom, after a relatively short set-up time, the entire audience was swirling their lasers into a collective sanguine dance of chaos onto the movie screen.

The screen then shifted the theater into space, where we (the audience), had to take our ship home, defend it from attacking ships, and build it up to defeat the big boss at the end. This was all achieved ingeniously by having our collective lasers point to specific areas of the screen to achieve these tasks. The trailer video below gives a good idea on what that is like:

1) Make sure what people are doing matters and don’t restrict them.

Simply being able to use a laser pointer was not the most amazing part of this game. It was visualizing all the demonstrable progress as the result of 100 people working together. Using the laser pointer was actually difficult in that you had to keep track of your own laser’s position amidst a crowd of other red laser dots — but it wasn’t impossible! The difficulty curve was just right to make the feeling of teamwork actually feel like an accomplishment.

The best part about this was the creator’s wish to have the entire audience be as loud and as directive as they wanted. None of the audience’s choices felt undermined or limited by the game or any other physical constraints. All decisions were controlled by popular votes and there weren’t enough trolls in the audience to break the game. The combination of all these factors led to an experience that was enjoyable and felt like an actual journey.

2) Don’t forget about the passive experience and sharing can work.

When I first heard that not everybody would receive a laser pointer, I felt a little disappointed but I realized this was a smart design choice. Holding up the laser pointer would actually feel tiresome after awhile and constantly figuring out where your laser pointer was in the crowd would likely be too taxing to do for a full hour. Being able to pass on the laser pointer became a really welcome mechanic because it allowed me to focus on the entire screen and look at the big picture.

I could see clusters of different people working together, people swirling their lasers around like maniacs, and trolls who weren’t even playing the game and were instead pointing at random people’s heads in the crowd. And this was all achieved without any direct communication amongst the crowd. The passive experience of watching all these elements together was just as entertaining as playing the game itself. In fact, they were completely different experiences and were likely designed as such.

The sharing was able to work particularly well due to the smart and clear phases between each level. Because the game was broken into multiple stages of building and battling, there were clear and logical points to switch off the laser pointer to another person. Sharing then became an obvious way to take a break in between all the action and it made anticipating your next turn and actions that much more exciting.

3) Make the interaction two-way: react to the crowd’s decisions

Although I think the presence of a commentator would ruin the game’s experience, I absolutely loved the snarky remarks the game had towards the decisions we were making. Towards the end of the game we decided to build another harvestor, an item we probably didn’t need any more of. Instead of warning against it, the game accepted our choice and reacted, saying “I don’t know why you would need another harvester…” and it gave everyone a good laugh.

The narrator also reacted to the level of our performance. When we weren’t doing so well in the game, it would say “Oh dear”. A slight jab but not disparaging in the least (you typically don’t want to put down your players). The very best part was when the audience was asked to decide to go to battle now or to reinforce their ship more. Although reinforcing was the obvious choice, the game called everyone out and said Astoria is filled with a bunch of cowards. Cheeky and great.

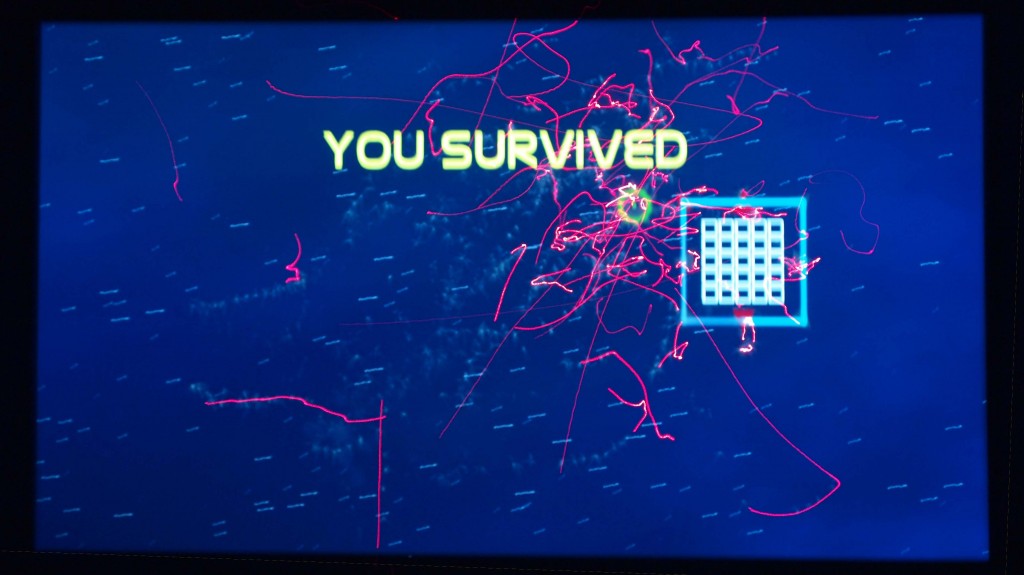

Having the game talk to the audience directly in the second person made the interactive experience a two-way street of communication. We engaged with the game and the game engaged with us, got a really engaging experience, and ultimately survived the space onslaught.

I hadn’t even heard of what Renga was until one of its creators was calling everyone around the festival to start lining up for it. After finally sitting down and beating the boss of the final game, I found myself in awe of everyone cheering, clapping, and swinging their laser pointers all over the room to do a victory dance. I truly had not done anything like that before and see endless possibilities for this level of interaction in the gamification industry.

This is really innovative. I love it.