Gamification, “the use of game play elements for non-game applications,” has taken the marketing world by storm, as companies use fun techniques to make their websites, social media, and mobile apps sticky, viral, and engaging to customers.

Gamification, “the use of game play elements for non-game applications,” has taken the marketing world by storm, as companies use fun techniques to make their websites, social media, and mobile apps sticky, viral, and engaging to customers.

While it’s a hot buzzword for today’s marketers, it’s hardly a new concept for teachers and trainers. In the early 1980’s the term “edutainment” came into vogue as software developers looked to create applications that would be both educational and entertaining. Their goal, three decades ago, was to marry children’s computer games and learning.

Two decades ago, in the early 1990s, Active-Learning (AL) became a much talked-about topic in the adult learning world, and has continued to grow in popularity since then. Active learning covers methods such as class discussions, “think-pair-share,” student debate, video discussions, role playing, and of course, game-play. In fact, during this time, Trainers Warehouse, has grown as the go-to source for creating tools, toys, and games to make learning more innovative, fun and effective.

Although the concept is not new, watching the evolution of Game-Based Learning (GBL) has been exciting. In grade school, I remember matching games were quite popular, as a method to learn vocabulary or concepts. 10 years ago, Jeopardy-like games were the go-to game paradigm for energetic, competitive learning reinforcement games.

Although the concept is not new, watching the evolution of Game-Based Learning (GBL) has been exciting. In grade school, I remember matching games were quite popular, as a method to learn vocabulary or concepts. 10 years ago, Jeopardy-like games were the go-to game paradigm for energetic, competitive learning reinforcement games.

Today, we look to games to do even more heavy-lifting—not just help to reinforce and remember information already presented, but we look to games as a way to introduce new information and engage the mind in fun, challenging, emotional, competitive, and memorable ways. As an example, see how third grade teacher, Mr. Pai, has transformed his class.

Finding Games

Ideas for games that support a variety of learning initiatives are everywhere – in books, in card decks, for sale online, for free in blogs and in social media discussion groups, for hire through consultants. Games seem to have been created to cover every topic under the sun — icebreakers or openers, teambuilding, communication, leadership, project management, process improvement, customer service, sales, marketing, banking, you name it.

Making Games

Making Games

If you can’t find a game already created for your content, you can create your own. Lots of “game guys” are out there waiting to create a snazzy customized game for you, complete with all the latest and greatest in game design. It will take some time and some “kish-cay” (my son’s term) – but it’ll be good. However, if that is simply cost-prohibitive, you can still “gamify” your training with popular game structures or “Frame Games,” (a term that Dr. Sivasailam Thiagarajan, a.k.a. “Thiagi” uses), consisting of generic shells into which you can load your own content, for instant customization.

Some games are geared toward information discovery—that is, learning new information. Others act as learning reinforcement and memory aids. Many do both. Following are some popular options.

Jeopardy-like games: This is my starting point, because it’s so popular and familiar. Although there are many free versions online, those tend to be loaded with advertisements and do not look particularly professional. The great thing about Jeopardy-like games is that they can be easily adapted for live, webinar, and online learning. They can also accommodate individual play, team play or “all-play” needs. Although Jeopardy is often perceived as a reinforcement game, you can also use it to introduce new material—starting and stopping the play to explain a new concept, explore nuances of an answer, or clarify confusion.

Other TV Game Shows: the vendors listed above also base learning games on TV favorites such as: Family Feud, Who wants to be a Millionaire? Wheel of Fortune, Money Taxi, Hollywood Squares, etc. You can easily add your own content into these games.

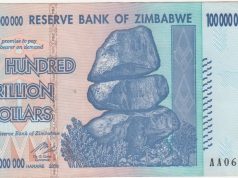

Points and Prizes: First, consider what behaviors you’d like to reward – participation, correct answers, timely attendance, etc.? Next, choose a currency to award when students display that behavior. It can be points, play money, self-made scratch tickets, raffle tickets, candy, tokens, or anything else collectible. At the end of your session, reward a prize to the winner and/or the one who’s made the best comeback.

Throwables: Balls connote game play. They can be used to call on individual contribution or team play. You can easily toss a ball around to solicit contributions. To make a game of it, set people into teams and reward points for correct answers, or take away points for “dropping the ball” with an incorrect answer.

Throwables: Balls connote game play. They can be used to call on individual contribution or team play. You can easily toss a ball around to solicit contributions. To make a game of it, set people into teams and reward points for correct answers, or take away points for “dropping the ball” with an incorrect answer.

Interactivities: Interactivity Games are a new style of participatory play developed for online learning. They are generally short and quick, and can be easily inserted into your online course, no matter what authoring tool you happen to use. Sports games, puzzles, flashcards, and Jeopardy-style games all translate well to the online learning environment.

What we can learn from Gamification

Clearly we have a myriad of options when it comes to training games. The question for us seems to be not whether to play, but what to play? and how to play? in order to maximize effectiveness. Be aware that the true Gamification experts optimize playing experiences for a range of player types, identified by Bartles as Killers, Achievers, Socializers, and Explorers. As trainers looking to simply engage our learners at a deeper level, we haven’t segmented our participants into Player Styles (we have enough industry debate Learning Styles!). Perhaps that’s our next challenge.

Meanwhile, let’s embrace the findings of our friends in the marketing department, who have done the research to know that game play is most satisfying when players get to:

- Compete (against themselves or others)

- Accumulate points or currency

- Move to increasing levels of difficulty

- Face new challenges and celebrate achievements

- View success and status on “leader boards” that show highest-ranking players.

Indeed, many of the games listed above are successful game experiences because they already employ many of these basic techniques. They are also effective learning techniques because the motivate participation, evoke emotion, challenge the brain and engage our minds.

However, like marketers, let us always keep in mind our reason for playing. For trainers, it’s not to win customers, build fans, or collect survey results – but our games do have a purpose. We are responsible for the growth and development of people. We must view games as engaging vehicles for learning and only select games that will achieve our desired learning results.

Susan Doctoroff Landay is President of Trainers Warehouse, where she is responsible for all Internet strategy, mailing, design, and other promotional efforts and oversees customer service activities. Her primary goal is to make training and learning more fun and effective. Prior to joining her father at Trainers Warehouse in July of 1997, she had several years consulting and training in the field of negotiation and business history consulting. She is a graduate of Yale University and received a graduate degree in management from the Kellogg Graduate School of Management at Northwestern University. Susan has written numerous articles, which have appeared in the Sloan Management Review, Pfeiffer Training Annual, eLearn Magazine, Smart Meetings, and Training Magazine.

I’m honestly getting tired of correcting people on this. I’ve been doing it for months and yet people continue to promote a core misconception about gamification. Using actual games (whether you call them serious games, edutainment, or anything else) is not the same thing as gamification.

As you note at the beginning of this piece, gamification is commonly defined as “the use of game play elements for non-game applications” or something to that effect. Despite the overreach by some gamification evangelists who have sought to envelope all uses of games under the gamification banner, that word “elements” is worth paying attention to. There’s a big difference between layering game play elements into a non-game experience, and making a game for a purpose other than just entertainment. These are fundamentally different design activities.

As an educator, designer, and researcher, there are a number of other things that I seriously disagree with in this article. I’m willing to let the rest of it go for today, but confusing learning games with gamification does a great disservice to educators who are trying to orient themselves to various uses of games for learning.

Moses:

I think your perspective is interesting, but I’m not sure what’s served by drawing the line you’re seeking to draw.

After decades of middling outcomes, the educational games and Gamification movements are off to the races. Our goal is to understand the ways in which these techniques and approaches can be used to improve outcomes for teachers, students and our nation as a whole.

As part of this Gamification movement, we have renewed interest, investment and activity – not to mention attention – being paid to your sector. These things do not in and of themselves improve outcomes, but they are necessary precursors.

My expectation – and I can’t imagine any parent, funder or politician disagreeing – is that we make every effort, use every viable technique, and leave no stone unturned in our effort to improve educational outcomes. To that end, I’d welcome your constructive participation in the dialogue!

What do you think are the real opportunities to use game-thinking and game mechanics to improve educational outcomes?

-Gabe

“My expectation – and I can’t imagine any parent, funder or politician disagreeing – is that we make every effort, use every viable technique, and leave no stone unturned in our effort to improve educational outcomes.”

Actually, many people — parents and researchers in particular — would disagree with the “use every viable technique” if there are known side-effects and consequences of those techniques. Specifically, the use of *external and introjected regulation* (the technical definitions of the specific form of extrinsic motivators common to gamification) to drive behavior in learners is well-proven to carry the potential for AMOTIVATION. In this case, short-term engagement that might even — temporarily — lead to improved test scores in the end can ultimately lead to even LESS motivation.

Unfortunately, the US public education system is already damaged greatly by a form of gamification (granted, not a “fun” one, but a gamified system nonetheless) that relies purely on external and introjected regulation, with the exception of teachers who are willing to risk their own career by stepping beyond the current standard-test-driven systems. But it is all a very complex system.

I think those who are against the rush to gamification in schools do not want to see us do MORE damage, and unfortunately, too many of the proponents simply do not understand the consequences so they are well-intentioned (“school is failing, shouldn’t we try ANYTHING??”) but just wrong. For example, if someone said your kids could take a medication that would instantly improve their “engagement” and get them “excited about the activities”, would that be a good thing? What if it, too, came with a long-term consequence of, among other things, permanent dependence on that drug…

The best long-term predictors of better performance and sustained outcomes from elementary school kids who then do well in college, are already known, and involve a combination of intrinsic motivation and, most importantly, (and most realistically) *identified and integrated regulation* (both forms of extrinsic motivation, but very different from the kinds of systems used in gamification). If we use gamification, it may come at far too great a cost.

As for the distinction between games and gamification, with respect to education/learning those distinctions are CRUCIAL. Games, especaiooy things like simulations, rely on precisely the kinds of motivators that are already linked to sustainable, improved outcomes while gamification relies on the kinds of motivators that have the opposite effect (long term). So, this matters. Deeply.

There are many uses of “game-thinking” that can be applied to improve learning, including but not limited to actual games (and of course not all games are going to be useful either, and especially the jeopardy-like “games” that have more in common with gamification than serious games). Much of what is being learned about quantified-self and feedback loops is extremely useful.

But the research keeps showing over and over again that the biggest problem with education is NOT the “style” or even speed in which it is “delivered”, but rather the appalling lack of perceived relevance. Trying to gamily it may add a “fun” sugar coating but does nothing to improve the underlying, fundamental problem (and relevance is linked to “identification and integrated regulation”, the best predictors of long-term educational outcomes for students). Meanwhile, gamification’s external regulators (I.e. The specific sub-type of extrinsic motivation known to have the underning effect) may lead to an even greater problem (hard to believe, given the sorry state) than we have now.

As a parent and former teacher (and game developer) and also the parent OF a teacher, I empathize 1000% with the desire to do something, ANYTHING, to make things better. But the science strongly suggests we could end up worse than we are now if we head down the gamification path. Worse, any resources spent in that direction are distractions from working on the things KNOWN to work. We need to focus talent and energy on making things better, not on making them *appear* better, and we need to avoid using a metric of “engagement” that fails to consider long-term implications.

[…] games? My reflections on how gamifying learning is both old and new, can be found on both the Gamification blog and […]

You have great insights about online business. I will surely come again. Thanks.

Amen to Mr. Wolfenstein for even attempting to draw a line between the apples and oranges here, and to Ms. Sierra for further calling out the problems at the heart of the oft-misguided gamification craze. This post is, first, yet another egregious example of misunderstanding the idea of “gamification”. Tarting up a multiple choice quiz (or a short answer quiz, like “Jeopardy”) does not “gamify” anything. The writer clearly does not understand the difference between gamification and playing a simple quiz game. That gulf between the two is wide and it is this kind of inaccurate information that creates further misunderstanding and confusion in the field. Understanding of basic game mechanics, and principles of intrinsic motivation are critical to understanding gamification, as are a grasp of the way they mesh with instructional design, and are completely lacking here. Further, the idea that layering cosmetics over simple recall tasks is in any way supporting learning is one of the things that makes most workplace training so ineffective. (Not that learning appears to be the goal here, as far as I can tell.) Further, the post appears to be a not-so-thinly disguised sales pitch for quiz templates. This kind of information does a disservice to those in the field who are trying to better understand REAL concepts and make useful application of them to their work.