I write and lecture a lot on the subject of how to improve customer and employee loyalty and engagement through gamification. Before kicking off the major gamification discussion in 2010, my background was in games but I was a huge loyalty nerd. I think this confluence of experiences helped inform my views on the power of gamification. Although they loyalty industry has been relatively slow to embrace gamification in all its power, a number of forward thinkers in the space (e.g. Air Canada, United, Marriott, Aeromexico) have done really interesting things – and we’ve profiled them here and at GSummit over the years. Though my views on loyalty are followed by many, I’m not immune to the issues of loyalty programs and their bad behavior.

So I figured I’d do a series on the other side of loyalty: the dark side if you will. Let’s look at some of the worst transgressions of the loyalty industry and try to learn from their mistakes. Even if you don’t work in loyalty, hopefully the lessons will be instructive as you think about how to engender engagement and loyalty in your customers and employees. Some of these issues are ameliorated with gamification while others really aren’t. As much as possible, I’ll try to be personal and constructive.

Destroying Loyalty Part 1:

Starwood’s Lies and Poor Expectation Management

I’ve been a loyal Starwood customer for nearly 15 years, the majority of those as a Platinum – until recently their highest earned tier. The company, whose brands include Westin, Sheraton, W and St Regis is generally known for their high degree of hospitality and innovation – although there has recently been major executive drama with the firing of their CEO. Despite their limited international footprint – I travel abroad a lot – I’ve remained loyal because of their consistently high(ish) quality.

Over the years however, I’ve come to the realization that the company and its employees lie. A lot. I’ve put up with much of the dishonesty because the overall service has been good, but recent interactions brought into focus what appears to be a widespread culture of “truthiness” at Starwood that has undermined my trust in the brand.

One of the core perks of SPG (as their loyalty program is known) is the Platinum upgrade. Providing you book directly with the company and not through a third party, SPG Platinum offers the following unambiguous language about upgrades on their site:

An upgrade to best available room at check-in — including a Standard Suite.

Even the information in the “full terms” section of their website, where most companies hide the “asterisks” is pretty clear and unequivocal.

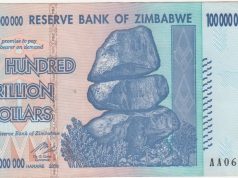

This clarity and simplicity have been one of the core brand promises of the SPG program, leading the company to many industry accolades, and a currency that has retained much of its lustre, despite devaluation. People – like me – believe(d) in Starwood.

But over the course of hundreds of hotel stays, I’ve encountered lots of friction about this commitment. In approximately 80% of my stays over the past 3 years, I have not been offered an upgrade. On its own, this is a disheartening number – and one that might give a frequent traveler pause. However, upgrades are not guaranteed and if they truly aren’t available at check-in, it’s simply a case of good yield management.

However, the problem with the majority of my stays is that upgraded rooms – including standard suites – were available for sale. Simply by launching the SPG app (and knowing the company runs a pretty tight, real-time availability ship), any guest can see exactly how many rooms are available for sale at any given time, and in which categories.

So, when I am not too tired from traveling to argue – I usually ask the nice person behind the counter if upgrades are available. In the 80% of cases where I haven’t been upgraded automatically, they say no without even looking at their computer. When I confront them with the info from the app, they first deny its existence, then – after some face-saving gesture – manage to find me an upgraded room. Of course, I wouldn’t press the issue if upgrades weren’t available, if only special suites were left or if the hotel was obviously super busy (as in a convention situation). But in most of the cases that’s not how I find myself – and the partial transparency of the app makes the occupancy situation pretty clear: e.g. if they have many rooms available at low prices, you can be sure they aren’t that full.

At the beginning, I used to complain more vocally about this issue both to the hotel and Starwood. After a while, I just priced in the idea that if I wanted my upgrades at SPG properties, ⅘ times I’d have to fight for it. In effect, I lopped 80% off the value of one of the major benefits of the program. However, I never stopped thinking about the divergence between the stated benefit and the reality, because I was confronted with it every time.

This “confrontation” actually made my interaction with the program pretty stressful. It has also taught me as a player that a negative behavior loop exists – if I choose to use it – that will usually get me what I want. The probabilistic loop looks something like this:

- Upgrade Denied (80% probability of failure)

- Push Back

- Upgraded Approved (90% probability of success)

The user gets what they want, but not without a battle. They learn over time that the squeaky wheel gets the grease and that the person across the counter from them has the power – and is using it arbitrarily. They are also taught that the “opponent” is lying, because the upgrade is in fact available when pressed. Overall, it’s a terrible terrible way to setup an interaction with users and results in a fair amount of frustration. But because it’s somewhat predictable, it also encourages “bad” behavior from the customer standpoint, and ends up making a mockery of the system.

In fact, in a post I made on Flyertalk asking for others’ experiences with SPG’s history of lying and deception around upgrades, even people who disagreed with my assertion about their dishonesty recounted experiences where they saw someone push back and get the upgrade. Though they decided not to push themselves for the benefit, the negative reinforcement loop works; everyone understands the lesson of how to get it.

Of course, the upgrade loop isn’t the only way the company acts dishonestly; as you’d expect, their ethical challenges extend far beyond just one loop. In a recent attempt to get a BRG (Best Rate Guarantee) from Starwood, I encountered the kind of misdirection that one would normally expect from a used car salesman. Without the other negative experiences, I might not have been as responsive to it, but it neatly fits a pattern of interaction for me.

Starwood’s BRG program allows you to submit a claim to the company if you find a lower price for a room on an alternative channel (e.g. Kayak, Expedia, etc.) Hotels pay big bucks – sometimes up to 30% – to third-parties to sell rooms, and the company would rather avoid these fees. It also wants to police its channels to ensure SPG.com has the lowest prices and partners aren’t dumping rooms. Their strategy is to use the “receipt or it’s free” gamification approach: offer the consumer a discount to find inappropriate behavior. So, if you find a lower advertised price and it can be verified, the company will give you a 20% discount off the lower rate or some bonus miles.

Never having done it before but curious about it, I submitted a claim. SPG responded quickly, denying the claim and saying the rate couldn’t be verified. So, a couple of minutes later, I booked the room – at the apparently unverifiable rate – and sent them proof. They then responded with a series of (entirely fabricated) reasons why the rate wasn’t the same. I responded by claiming that was false and getting the social media team involved. Magically, they then found the exact same rate I found without ever admitting that they were deliberately trying to skirt their own policies.

You can see the full thread of my discussion with them – including their entirely false and deceptive claims right here (read from bottom to top).

Obviously, I’ve lost a tremendous amount of faith in the Starwood program and its ability to deliver on brand promise in a transparent way. They have spent all of my accrued loyalty in a single set of interactions, leaving me to cancel my forward bookings and renounce my strong Starwood preference.

You can avoid having these issues in your engagement system by following a couple of alternative approaches that are used in other loyalty programs, and particularly in gamified systems:

A. Transparent Expectation Setting: Airlines have worked hard to make upgrades more predictable and less stress-inducing for users. Their upgrade systems are more “transparent”, while also more complicated. For example, upgrades are always based on availability, and usually prioritized further by something like status, fare paid and time added to the upgrade list. Major carriers generally post their upgrade algorithms to their websites to help explain how they do it. In recent years – begun by United – they have also taken to posting a leaderboard at the gate with the list of eligible upgradees. This leaderboard shows the number of upgrade seats available (booked/checked in), and the “masked” list of people waiting for an upgrade. This way, if there are 10 upgrade seats left, and you are number 50, you know you won’t be getting one. If you are number 2, you pretty much know you got it. And if you are numbers 8-12, the countdown to departure is pretty exciting/tense.

Like an elevator display that shows the floors as you progress, this kind of leaderboard design is stress reducing for most participants – even as it can produce some anxiety for those on the margin. In fact, it’s been so successful that most airlines have followed United’s lead in moving it to their mobile apps, so you can see the leaderboard in the palm of your hand and set your expectations accordingly.

Hotels don’t have the defined “departure” time of airplanes, and the current Starwood policy is clearly intended to leave more discretion for the individual property. However, if a leaderboard isn’t appropriate (and I think it could be) – a notification system would be helpful here. Send everyone an email the night before with some upgrade status information. If you’ve received an upgrade – confirm it. If you haven’t, tell people they are not in the running. If you want to use upgrades to prompt additional revenues, offer people on the margin a chance to upgrade for cash, jumping the queue. This does not preclude the property from giving folks a spontaneous upgrade on arrival, but it would reset expectations.

Even more transparency (like an upgrade leaderboard) would be possible with technology advances that get better at predicting revenue and occupancy – and much of this could be automated. Adding additional criteria like rate paid, etc. could only serve to make the system function better.

B. Surprise & Delight. The other way of handling upgrades is to shift them to pure surprise and delight mode. This means removing the chance of earning one through a structured set of actions (earn and burn) and shifting it to a slot machine mechanic. Other loyalty programs (like Hyatt) effectively do this by only promising upgrades that offer better features (e.g. views) without specifying any structured category increases/improvements. Although this might be seen as a big loss or uncompetitive, advanced AI software could be used to make it more sophisticated and effective. For example, software could predict when you’re likely to be “tired” of not getting the upgrade, and give it to you. It could read your social media and know if your trip is a special event, if you’re not feeling well or if you just won a big client pitch and reward you accordingly.

Moreover, upgrades could take many different forms – and by removing expectations, this could improve flexibility and responsiveness. If I really like views, you could tailor the experience appropriately. Some companies (Starwood included) are trying to do this now by asking you for preferences on profile information, but without the backend intelligence, the system isn’t going to work especially well.

Obviously, more surprise and delight would also produce more social media engagement around the upgrades themselves because they would be a bigger deal. Today, losing an upgrade is more newsworthy than getting one. This is the wrong posture for companies in a competitive, user-referred environment. On the whole, rather than creating a fight out of it, lowering expectations and then using intelligence could make the upgrade experience much more fun.

C. Simplification of Rewards: In the case of the Best Rate Guarantee system, the company is doing too much to validate the user’s input before issuing the reward. They do a good job of being responsive – at great cost to the company I’m sure. But Starwood has fallen into the over-engineering for “gaming the system” trap that befalls many creators of reward systems.

Instead of validating BRG claims, the company could easily restructure the program and simplify everyone’s experience. Ask users to take screenshots and give them points instead of money only. Automatically award the points and do spot-checks after. Build a small amount of intelligence that looks for repeat users of the system and flags them for a manual inspection. If that doesn’t feel like enough of an incentive, turn BRG into a sweepstakes: every discrepancy you find gets you a small perk on that hotel stay (e.g. some free wine) plus an entry into a sweepstakes to win 1,000,000 points. This reduces auditing requirements as the company only really needs to validate the winning entrants.

Above all, assume your customers are not idiots and are not lying to you, and make sure the system is engineered first for engagement – and only later for anti-gaming. Definitely make sure staff aren’t under the gun to invalidate claims no matter what.

Overall, many of Starwood’s issues here are about culture and structure. As a brand operator with mostly franchisee hotel owners, SPG can only do so much to ensure good behavior. But if the systems of engagement – notably the loyalty program – are undone with hundreds of small lies and the company doesn’t re-engineer to adjust for them, eventually users like me will go off the reservation. Our conclusion: the company is dishonest and the brand doesn’t deliver on its promises. Clearly, some of this is also about training front line staff as well, but mostly those issues would be well resolved with structural changes.

Expectations and honesty matter tremendously in loyalty. Failing to manage these appropriately can be fatal.

In our next chapter, we’ll look at the issue of benefit reduction and how to avoid it.